Had you attended the funerary feast of the ancient Phrygian King Midas, around 800BCE in what is now central Turkey, you would have eaten lamb and lentil stew. The archaeological site was first discovered in the 1950's, but it wasn't until 1998 that a chemical archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania Museum, Dr. Patrick McGovern, had the technology to analyze cook-pot residues.

He found a drink made of a mixture of grape wine, barley beer and honey mead. (In both the Iliad and the Odyssey, Homer describes a drink made from wine, barley meal, honey, and goat cheese). Small jars contained fatty acids and lipids associated with sheep or goat fat; phenanthrene and cresol, suggesting the meat was barbecued before it was cut from the bone; gluconic, tartaric, and oleic/elaidic acids implying the presence of honey, wine and olive oil respectively (perhaps a marinade?); and a high-protein pulse, likely lentils. Traces of herbs and spices completed the dish.

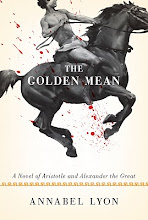

Despite its far-reaching spider web of trade routes (particularly in the wake of Alexander's great Eastern campaigns), the ancient world was made up largely of locavores. (We moderns think we're so trendy!) A typical Macedonian diet in Aristotle's time would have featured a lot of bread and fish, and seasonal fruits and vegetables. (Both Alexander and his father, Philip, were supposed to have had a passion for apples).

Meat was a luxury unless you were extremely wealthy. Goat and mutton were most common; chicken, duck, goose, and rabbit were also available; beef was rarely eaten. Staple proteins were beans, eggs, cheese, yoghurt, and nuts. Wine was brewed far stronger than we know it today and was usually served with water, as we'd serve scotch. Barley beer was popular in Macedon, less so in warmer, sunnier southern Greece, where grapes were more plentiful.

Alisa Smith and J.B. MacKinnon's Vancouver-centric The 100-Mile Diet: A Year of Local Eating was surprisingly helpful when I tried to picture an ancient kitchen. It made me think about all the foods I took for granted that Aristotle would never have heard of (black tea, coffee, mangoes, sugar, pepper, salmon, chocolate, etc.). It also made me think hard about food storage and seasonal availability; at one point I caught myself giving my characters a meal of roast lamb in autumn--whoops. In the final draft, they get goat.

Historical novelists like to describe food. It's a double urge, I think: to surprise the reader with the sophistication of the era they're describing, and to make the period instantly accessible. How hard is it to imagine sitting down to a plate of feta and walnuts, or a nice, spicy lamb-lentil stew and a beer?

A couple of websites featuring approximations of ancient Greek recipes are ancientgreekfood.net and greek-recipe.com.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment